Introduction

This is a work in progress — a very early stage of progress.

The author isn’t an expert in Japanese, though he does know enough to get by.

As they say: if you really want to learn something, try teaching it to others. The process of creating this system helped him to learn quite a bit more (it took a lot of discussion with more knowledgeable people).

Regardless, errors are still likely. Proceed with caution!

This site explains how to create sentence diagrams for Japanese sentences.

These simple “stick diagrams” are a teaching aid to visualize the grammatical structure of individual sentences. They can be drawn by hand and don’t require any software or special tools to create.

Anyone can read and understand these diagrams. They don’t require any familiarity with linguistics or grammatical vocabulary to understand (though some grammatical knowledge is required to create them).

The system is particularly beneficial for intermediate Japanese learners who wish to better understand the grammatical composition of Japanese sentences.

This site does not attempt to teach any significant fraction of the Japanese language nor its grammar, it only introduces a tool to aid further study.

What’s a Sentence Diagram?

Americans of a certain age might remember diagramming sentences while learning English grammar in primary school.1

The author was one of those annoying nerdy kids who loved them! He wondered if it wouldn’t be possible to create something similar for Japanese sentences.

Sentence diagrams display the structure of sentences to language learners, without resorting to arcane grammatical jargon. They visually display the internal structure of a sentence, breaking them into simple pieces that show how a sentence works. They show the core of the sentence, as well as which parts modify or further describe which other parts.

They don’t explain precisely what a sentence means, however (you still need to understand the meaning of the Japanese words they contain).

Anyone with a minimal understanding of English can view an English sentence diagram and immediately understand the basic information presented, even if they don’t know a noun from a verb.

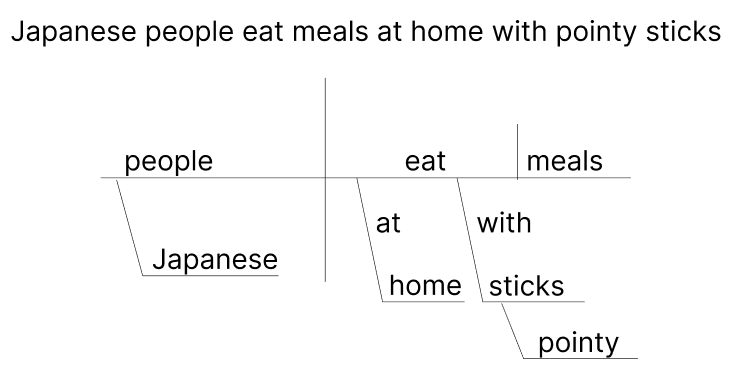

Here’s an example (using the English diagramming system that won’t be explained further):

The original sentence is shown at the top: “Japanese people eat meals at home with pointy sticks”.

The large horizontal line shows that the fundamental “core” of that sentence is “People eat meals”.

The subject, verb, and object in that core sentence are indicated by the vertical lines that separate them, but you don’t need to understand those words to understand the diagram! You only need to understand the few simple words present on that line in the diagram.

The diagram clearly shows that the “action” part of the sentence (“eat”) is modified by a bunch of other words. They eat “at home” and “with sticks”.

The word “pointy” modifies or further describes the word “sticks”. Similarly, the word “Japanese” modifies “people”.

Syntax, not semantics

Note that sentence diagrams make no attempt to explain what a sentence means. They only display how the various parts go together structurally. The linguistic/grammatical jargon for this distinction is “semantics” (what it means) vs. “syntax” (the structure).

Sentence diagrams only show syntax. On their own, they cannot explain subtle differences in nuance or meaning!

If the English sentence above was rewritten as:

At home, Japanese people eat their meals with pointy sticks

the diagram would be identical even though it has a slightly different nuance.

The diagram for this reordered sentence would be absolutely identical because the sentence structure, what modifies what, remains the same.

But the reordering imparts a different nuance: This new version emphasizes ”at home” more than “Japanese people” (possibly implying that they use their hands or knives and forks elsewhere — how rude!).

That’s a semantic difference, not a syntactic difference. It isn’t represented at all in a sentence diagram.

Why diagram?

There are two primary reasons to diagram:

-

Viewing provides a vehicle for further discussion (for teaching). A teacher might, for example, want to contrast two different ways to express something (with different sentences/diagrams). Alternately, they might just want to show correct and incorrect ways to parse a given sentence.

-

Creating diagrams provides a tool for students to decipher potentially complex sentences on their own. Creating sentence diagrams is an excellent way for beginners to reason about a sentence and better understand how the grammar works.

文章図式 (Japanese sentence diagrams)

This site is for English-speakers trying to learn Japanese. It describes a system to create Japanese sentence diagrams, or 文章図式 (pronounced “bunshouzushiki”). The author hopes that Japanese sentence diagrams will help other beginners to better understand the language.

The Japanese word for “sentence” is 文章 (bunshou, literally “writing section”). One word for diagram is 図式 (zushiki, literally “diagram method”). “Bunshouzushiki” s quite a lot to type in Roman characters, so this site omits the “shou” and and the “shiki” and just calls them “bunzu” (文図) for short.

Minimal jargon, but Japanese jargon

The author has done his best to avoid technical jargon whenever possible, but it’s impossible to describe how to create these diagrams without resorting to grammatical terminology at many points.

Whenever possible, this site uses Japanese grammatical terms (with translations) rather than the English terms alone. For example,

猫 (neko or “cat”) is a 名詞 (meishi or “noun”).

The reason is that there are often subtle differences between the Japanese and English concepts. Ultimately the grammar terms are just names for concepts. Since the Japanese concepts are intended, it makes sense to use the Japanese terms rather than force-fitting the English terms.

The word “noun” means pretty much exactly the same thing as 名詞 (a “named part of speech”) but this won’t always be the case. “Adjectives”, for example are a whole ‘nother ball of wax.

Some Japanese required

This site is aimed at “intermediate” Japanese learners (whatever “intermediate” means).

While it hopes to prove useful even for beginners, it does assume some basic knowledge about the language.

Just as an 11-year-old studying grammar for the first time already speaks their native language to some degree, these diagrams also presume a minimal familiarity with Japanese (though less than an 11-year-old Japanese native might possess!).

In particular, some familiarity with the writing systems is mandatory. You should be able to read hiragana and katana (the phonetic writing systems). The linked resources from Tofugu are excellent, and should suffice for much of the content here.

It’s hard to make sense of Japanese sentences using hiragana and katakana alone, however (not to mention space-consuming). So most of the example sentences use at least some kanji (Chinese pictographic characters).

Whenever possible, this site uses common words and simple sentences, but readers must at least know a few hundred common words and be able to construct very basic sentences in Japanese.

The author recommends getting through at least the first three (free!) levels on https://wanikani.com (or something equivalent) before attempting to use this site.

Romaji (phonetic roman letters for Japanese words like “bunshou” and “zushiki” above) are only used on this introductory page. The remainder of this site only uses furigana (small kana characters above kanji) where appropriate.

Footnotes

-

The English diagramming system appears to have been named the “Reed-Kellog” system at some point.

Wikipedia claims the system has been “discouraged in favor of more modern tree diagrams”, but the citation offered as evidence isn’t terribly convincing. The cited article says that tree diagrams are “favored by linguists” and notes in their comparison that “it must be admitted that the purposes are slightly different”.

This author feels they still have their place. One great thing about sentence diagrams is they can be immediately understood by a layman. They don’t require any familiarity with technical grammatical terms. ↩