Foundations

Units of composition

These are the basic units or divisions of Japanese writing, from largest to smallest:

文章 Writing in general

An article, composition, essay, or, an individual sentence.

段落 A paragraph

Literally, “falling columns” of text.

文 A sentence

Something that can be delimited with a period.

文節 A clause

An individual clause or phrase within a sentence.

単語 An individual word.

We are only concerned with 文, 文節, and 単語 (sentences, clauses/phrases, and words). In particular, identifying the “core” 文節 in a sentence is the most critical part of diagramming.

One caution: while the term 文章 is often translated as the English word “sentence”, the word 文 more accurately reflects the English concept of a sentence (something that ends with a period, question mark, or exclamation point).

文節 (clause) sub-parts

Subjects and predicates

文節 (clauses) are by far the most important grammatical constructs when diagramming.

Every fully-formed 文 (sentence) contains at least one 文節 (clause). Many only have one, but complex sentences might have many.

Every 文節 contains two parts:

主語 Subject

This is the “master” of a clause. It’s the doer in a clause (or the “be-er” in a clause that describes existence, nature or state). The 主語 is not always explicitly present, it’s often implied. (There’s always a logical subject, but it isn’t always explicitly stated.)

述語 Predicate

The predicate in a clause describes what’s happening. It expresses an action, existence, or nature/state. The 述語 will always be at least partially explicitly stated in every clause.

述語 in particular are the most critical part of any Japanese sentence. You can literally omit everything else, but every sentence always provides an explicit 述語 (predicate).

Every clause always has a logical 主語 (subject) and 述語 (predicate)! The 主語 might be implied, but the 述語 will always be explicitly present.

These two parts form the framework of every clause.

Subsidiary parts

The remaining sub-parts of a clause fall into one of the following three categories:

修飾語 Modifiers

Words that modify or qualify other parts of the clause.

- 「ゆっくり歩く」(”slowly walk”)

接続語 Conjunctions

Words that connect distinct clauses or clause-parts.

- 「安いのに、おいしい」 (”it’s cheap, but it’s delicious”).

独立語 Interjections

Independent words.

- 「さあ、やろう」 (”hey, let’s do it”)

Parts of speech

The Japanese words for “parts of speech” is 品詞.

The character 詞 means “a part of speech.” It’s used to indicate a grammatical type or function, and doesn’t refer to individual words or categories of words themselves.

The characters 言 or 語 refer to instances or groupings of words, while 詞 indicates parts-of-speech (the type of a group of words) specifically.

Most of us are familiar with the English parts-of-speech called nouns and verbs. Unsurprisingly, Japanese has both of these as well, but the Japanese names are:

名詞 Noun

Literally: a “named part of speech”.

動詞 Verb

Literally: a “movement/change part of speech”.

Including these, Japanese has ten total parts of speech, broken into three major categories.

The parts-of-speech taxonomy

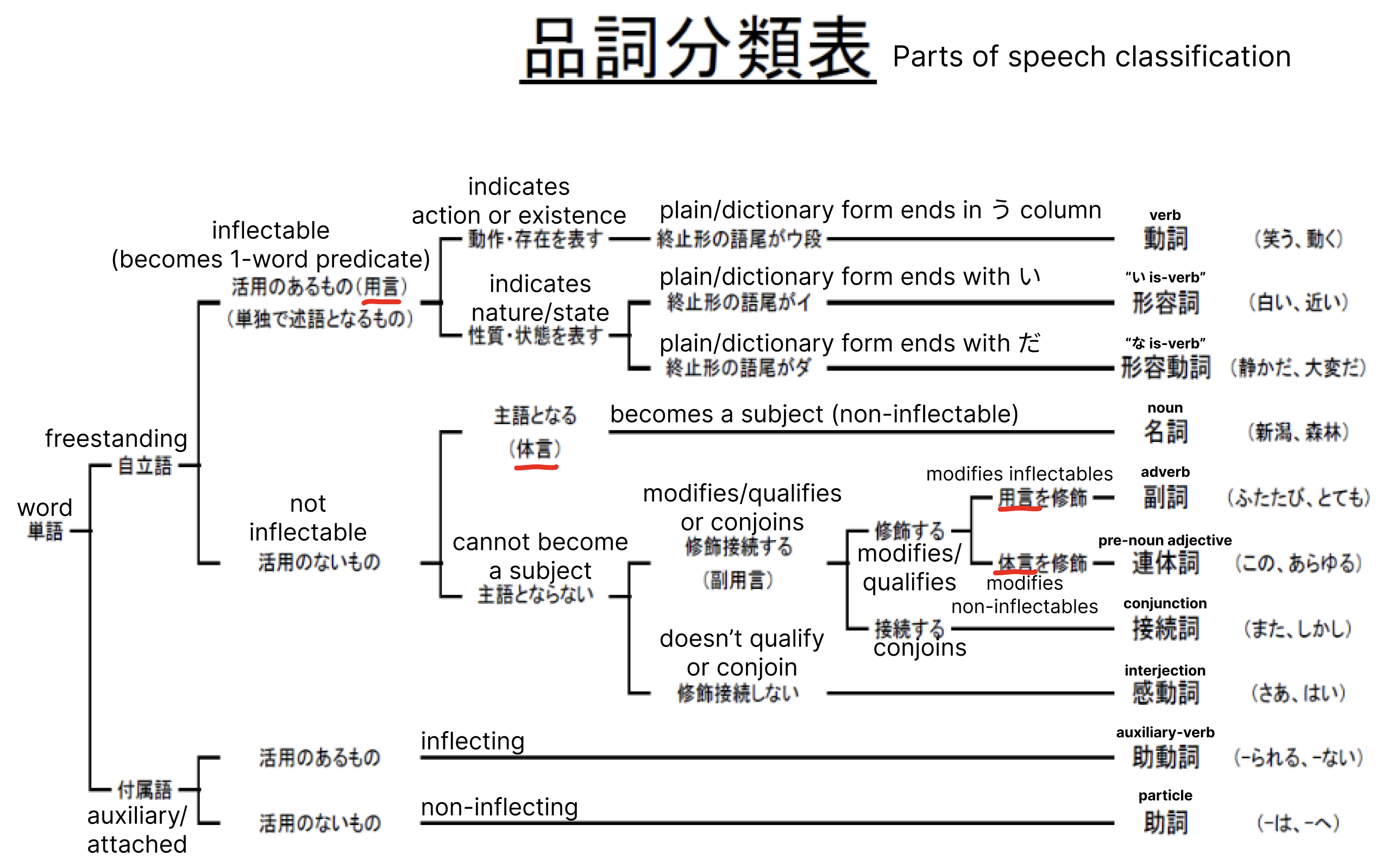

The following diagram provides an excellent synopsis for the ten parts of speech. Refer back to it often:

Many Japanese grammar resources only refer to eight parts of speech (八品詞). The diagram above also includes two additional types for auxiliary verbs and particles that can’t be used by themselves.

The ten parts of speech are broken into three major categories:

-

用言 are the most important category.

Grammarians call these “inflectable” or “declinable” words that are used in the predicate. Honestly, the Japanese characters are easier to understand: 用言 means “use words” or “utilization words”. They’re used to do things.

-

Non-inflectable words, or freestanding words that aren’t 用言.

The most important of these are 体言, words that can become subjects. All 体言 have a type of 名詞 (noun)

-

Auxiliary or attached words-suffixes

We will describe each of these categories in turn.

用言: predicate words

用言 are by far the most important part of a sentence. Japanese often omits or implies everything else, but there will always be at least one 用言 explicitly provided to tell you what’s happening in the sentence.

Note that 用言 are underlined in red in the parts of speech diagram above.

Japanese has three parts of speech in the 用言 category:

動詞 Verbs

The plain or dictionary form of these words will always end with a sound from the う column of the kana charts.

- 笑う (to laugh)

- 行く (to go)

形容詞 Is-verbs

Most English-language resources call these “adjectives” or ”い-adjectives” (because they always end with the kana character い).

Because Japanese themselves consider 形容詞 a form of 用言, however, this site strongly prefers to think of them as “is-verbs” or ”い is-verbs”.

They are single words that specify a subject’s state or nature. In other words, they say the subject ”is something”, but they don’t need to add another word to do so: the “is” is part of itself.

- 白い (is-white)

- 近い (is-near)

形容動詞 だ Is-verbs

Similarly, English-language textbooks on Japanese grammar usually call these “な-adjectives”, or “nominalizing adjectives”. This site prefers “だ is-verbs” for is-verbs that are formed with the suffix だ.

- 静かだ (is-quiet)

- 大変だ (is-terrible)

These three word-types all function like verbs do in English. Technically, only 動詞 is literally translated as “verb”, but all three types function like verbs. They are the part of a predicate that explain what’s happening.

SVO vs. SOV

English tends to focus on the who and what within a sentence, while Japanese tends to focus on the action or state.

English is often described as an “SVO” grammar (subject, verb, object in that order). For example, the sentence: “I eat it” contains the subject “I”, then the verb “eat”, and finally the object “it”. We tend to focus on the first word of that sentence: “I”.

Japanese is often described as “SOV” because the verb comes at the end. They tend to focus on the last word of a sentence, the verb.

This site believes Japanese is better considered an “SV” language. It sometimes even acts like just a “V” language!

In Japanese, “I eat it” (the exact same thought from above) would normally be expressed as just:

「食べる」

This is still a complete sentence, even though it’s only a single word!

The subject “I” and object “it” are implied. Japanese grammar rules allow them to be omitted since they aren’t necessary for understanding. Explicitly adding the extra words (私があれを食べる) would sound wordy and weird.

Implied words can be omitted

Imagine offering food to a hungry Tarzan. If he replied with an enthusiastic “Eat!” (or 「食べる!」 in Japanese), would you have any difficulty understanding that he will eat the food you were offering?

English grammar explicitly requires words that, strictly speaking, aren’t necessary.

The words “I” and “it” would be unnecessary for comprehension. The verb “eat” communicates all we need to know, but English grammar rules pretty much mandate that we provide the unnecessary words (else we sound like Tarzan).

Japanese doesn’t work that way! (Which makes one wonder how Tarzan-speech is represented in Japanese manga.)

Japanese is a denser language. It’s more efficient because it allows you to omit unneccesary pronouns like “I” and “it”.

体言: subject words

体言 literally means “body” or “subject” words.

体言 are “substantive” words that can become the 主語 (subject) of a sentence. They are “things” rather than actions/existence/nature/state.

Note that 体言 are underlined in red in the parts of speech diagram above.

There is only one grammatical type for 体言:

名詞 Nouns

This is the only type in this category that can become a subject.

- 新湯 (freshly-poured-hot-bathwater)

- 森林 (forest; woods)

Other grammatical types

There are four remaining grammatical types that are neither 用言 nor 体言:

副詞 Adverbs

These modify or qualify 用言.

- 再び (again)

- とても (very; awfully; exceedingly)

連体詞 Pre-noun adjectives

These modify or qualify 体言.

Jargon is hard to avoid with this part of speech. They are closer to the English concept of “determiners” or “definite/indefinite articles” like “the, “this”, or “every”. They only modify nouns and can’t act like verbs.

- この (this)

- あらゆる (every)

接続詞 Conjunctives

These connect clauses or parts of clauses together.

- また (and; in addition)

- しかし (however; but)

感動詞 Interjections

These express excitement, call for attention, or act as greetings/acknowledgment.

- さあ (come; here; all right; well; ah; actually)

- はい (acknowledged; understood)

Word-suffixes

These auxiliary word-suffices aren’t standalone words, but things that attach as suffixes to other words.

There are two types:

助動詞 Auxiliary verbs

These are suffixes that “inflect” or “conjugate” other verbs to modify the meaning.

- 〜られる (expresses potential)

- 〜ない (expresses negation)

助詞 Particles

These indicate the function of preceding words or other clause parts.

- 〜は (topic identifier)

- 〜へ (direction identifier)

Other word categories

There are three more categories of words that we’ve not described so far:

指示語 Pointing words

These are also known as こそあど language. There is no good English equivalent to describe these because they can function as any of several different grammatical types: 名詞 (nouns), 連体詞 (pre-noun adjectives), 副詞 (adverbs), or 形容動詞 (だ “is-verbs”).

Things close to the speaker use the こ forms: ここ、これ、こちら.

Things near the listener use the そ forms: そこ、それ、そちら.

Things far from both the speaker and listener use the あ forms: あそこ、あれ、あ ちら.

Undecided/unsettled things use the ど form: どこ、どれ、どちら.

複合語 Compound words

These are single words formed with two or more other words. They can be nouns, verbs, or い “is-verbs”:

-

複合名詞, e.g. 春+風 → 春風 (a spring-breeze)

-

複合動詞, e.g. 旅+立つ → 旅立つ (beginning-a-trip)

-

複合形容詞, e.g. 心+細い → 心細い (is-anxious)

Regardless of form, these are single words in Japanese. They should never be broken apart in a diagram. There aren’t any separate modifiers: they are individual compound-words, not a modifier plus another word.

-

派生語 Derived words

There are two sub-categories of derived words, prefixed words and suffixed words:

-

接頭語 (prefixed words), e.g. お米 とり調べる か弱い

-

接尾語 (suffixed words), e.g. ぼくたち 春めく 子供らしい

Like 複合語, 派生語 can be nouns, verbs, or い “is-verbs”. They are also individual words that should never be broken apart in a diagram.

-

Summary

The most important categories of words are 用言 and 体言:

-

用言 literally means “use words”. They include three different parts of speech: not only 動詞 (verbs), but “is-verbs” like 形容詞 and 形容動詞 as well.

-

体言 literally means “subject words” or “body words”. They are always 名 詞 (nouns) or things that have been “nominalized” to act like nouns.

Every clause has a 主語 (subject) and a 述語 (predicate).

品詞 are parts of speech. They are grammatical types rather than individual word instances or groupings/categories of words. There are eight “freestanding” parts of speech (we will describe rules for diagramming each elsewhere on this site).

Things like compound words and derived words should not be broken apart in a sentence diagram. They should be considered as individual units.